CAMBRIDGE, MA 1961 - 1962

In the spring of 1961 Ruth and I decided to get married and I needed to think beyond making fake antiques. In June 1958 Life magazine had run an article about two Italian artist brothers working in the US. One of them, the sculptor Mirko Basaldella (1910-1969), was giving workshop courses in design at Harvard in the School of Architecture. I had liked his work shown in the Life article enough to have saved the issue, and decided to apply to the School of Architecture to be able to work with Mirko.

When I went to Cambridge, I was told that the enrollment period for the School of Architecture was closed, but I could still try the Graduate School of Education. So I walked over to the Ed. School and there I was encouraged to apply and even offered the possibility of a scholarship. There were basic education courses I would have to take (though I was able to “achieve” them by passing their tests without taking the courses themselves), but I was entitled to sign up for any number of courses at the University for credit toward a Masters of Arts in Education. I was eventually admitted, and took design courses with Mirko and worked with him independently as a part-time apprentice.

The design studios were in an old abandoned bindery building overlooking the Charles River, with great lighting from huge factory windows and an open-space floor plan. The courses Mirko taught were in the tradition of Bauhaus methods that influenced design courses in many American universities at the time. But he approached design not from an architect’s or industrial designer’s point of view but from a sculptor’s feeling for form and expression.

In the spring of 1961 Ruth and I decided to get married and I needed to think beyond making fake antiques. In June 1958 Life magazine had run an article about two Italian artist brothers working in the US. One of them, the sculptor Mirko Basaldella (1910-1969), was giving workshop courses in design at Harvard in the School of Architecture. I had liked his work shown in the Life article enough to have saved the issue, and decided to apply to the School of Architecture to be able to work with Mirko.

When I went to Cambridge, I was told that the enrollment period for the School of Architecture was closed, but I could still try the Graduate School of Education. So I walked over to the Ed. School and there I was encouraged to apply and even offered the possibility of a scholarship. There were basic education courses I would have to take (though I was able to “achieve” them by passing their tests without taking the courses themselves), but I was entitled to sign up for any number of courses at the University for credit toward a Masters of Arts in Education. I was eventually admitted, and took design courses with Mirko and worked with him independently as a part-time apprentice.

The design studios were in an old abandoned bindery building overlooking the Charles River, with great lighting from huge factory windows and an open-space floor plan. The courses Mirko taught were in the tradition of Bauhaus methods that influenced design courses in many American universities at the time. But he approached design not from an architect’s or industrial designer’s point of view but from a sculptor’s feeling for form and expression.

Mirko Basaldella in Cambridge

I worked with Mirko for a couple of years, and Ruth and I visited him at his summer home in Forte dei Marmi in Tuscany in 1962.

Mirko taught me to think of sculpture in terms of construction as opposed to carving or modeling. The modern tradition of this approach came from Picasso’s 1913-1915 paper and wood constructions of guitars and bottles, through Gabo and Pevsner’s later constructions of purely abstract forms.

Mirko taught me to think of sculpture in terms of construction as opposed to carving or modeling. The modern tradition of this approach came from Picasso’s 1913-1915 paper and wood constructions of guitars and bottles, through Gabo and Pevsner’s later constructions of purely abstract forms.

Sculptures by Picasso, Gabo, and Pevsner.

Mirko added a sense of mythology and formal suggestions of totemic presences, along with a knack for exploring and discovering forms in various materials.

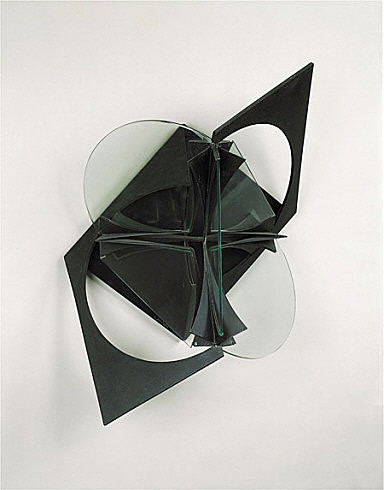

Sculpures by Mirko Basaldella

Here are two of my pieces from that period, both of a totemic–figurative form, and from unusual sources: an egg carton and parts of a broken piano’s inner mechanism.

Egg Woman c. 14” high Piano Man 22" high