SOME THOUGHTS ON MICHELANGELO'S LAST SCULPTURE : THE RONDANINI PIETÀ

An essay from my book, MAKING ART: A MEMOIR, The First TwentyFive Years

An essay from my book, MAKING ART: A MEMOIR, The First TwentyFive Years

Michelangelo Rondanini Pieta marble 1552-1564

Sforza Castle, Milan

Sforza Castle, Milan

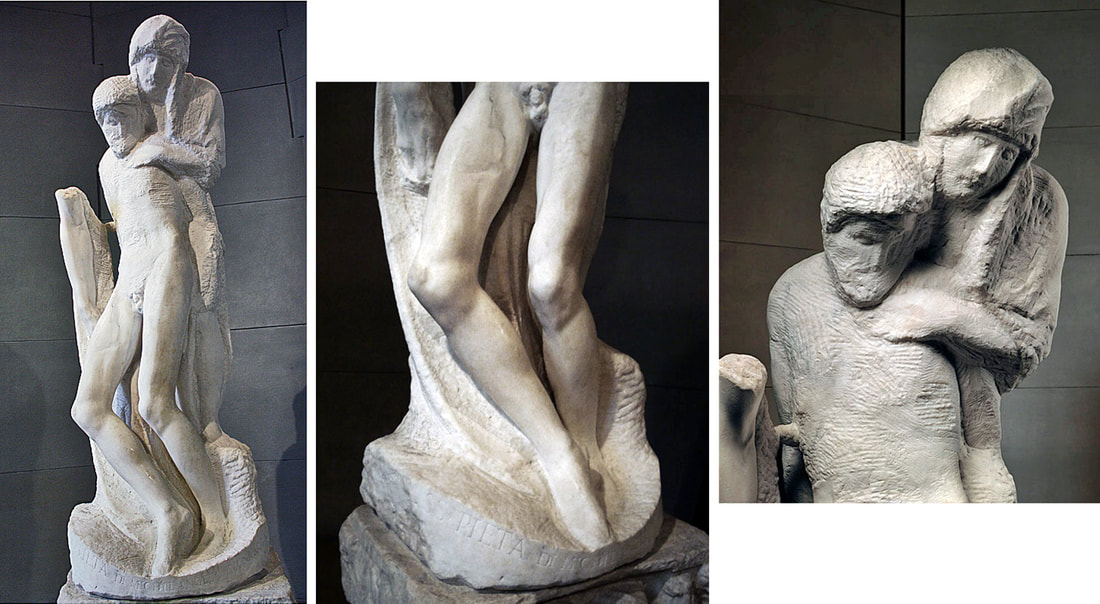

The Rondanini Pietà is Michelangelo’s last sculpture. He worked on it until a few days before he died – just a few weeks before what would have been his 89th birthday. It was a work in process, its character drastically changed from an earlier incarnation when Michelangelo removed the connection of Christ’s right arm from a much more robust upper torso, leaving the arm still visible but separate from the now rough and narrow torso. This work is a kind of hinge in art, the visible transition from one mode of visual thinking to another.

SOME BACKGROUND ON THE THEME OF THE PIETÀ

Like many elements of the biblical texts that are known to be based on the stories of older cultures, the stories of Christianity grew from and expanded the narratives collected in what has come to be known as the New Testament. The word Pietà, which comes from the Latin pietas, meaning pity or compassion, has come to refer to an image of the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of her son Jesus, after he was taken down from the cross of his crucifixion.

The scene of the Pietà is in none of the four Gospels, and of the four Evangelists only John even mentions that the Virgin Mary was at the crucifixion, as almost an afterthought to his story about the garments of Jesus that the soldiers took as a bounty:

JOHN 19 (All Biblical quotes are from the King James Version.)

23 Then the soldiers, when they had crucified Jesus, took his garments, and made four parts, to every soldier a part; and also his coat: now the coat was without seam, woven from the top throughout.

24 They said therefore among themselves, Let us not rend it, but cast lots for it, whose it shall be: that the scripture might be fulfilled, which saith, They parted my raiment among them, and for my vesture they did cast lots. These things therefore the soldiers did.

25 Now there stood by the cross of Jesus his mother, and his mother's sister, Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene.

It is no surprise that the details in the narratives of the four Gospels differ from each other. Had four trained reporters been eyewitnesses at the crucifixion of Jesus, working for different newspapers, their reports would have been different in both the style and the details presented or omitted.

As we now know after much biblical research, none of the Evangelists was present at the crucifixion, and their stories were written down many years later, at different times, from 70 to over 100 years after the event, the later ones building on the earlier versions.

As the crucifixion of Jesus became the central icon of their faith, Christian writers and artists began a centuries-long elaboration on the elements of the Gospel stories. The visual interpretations of the story developed over the many centuries along with the complex history of the Church and its growing and changing liturgy.

In the Gospels’ narrative of the crucifixion, from the death of Jesus to his burial in the tomb, there developed and evolved a sequence of episodes (following his death on the cross) that was envisioned in art as the scenes called the Deposition, the Lamentation, the Pietà, and finally, the Entombment.

One person that all four Gospels mention in their narratives of the crucifixion is Joseph of Arimathea.

This is John’s version of the burial of Jesus:

38 Later, Joseph of Arimathea asked Pilate for the body of Jesus. Now Joseph was a disciple of Jesus, but secretly because he feared the Jewish leaders. With Pilate’s permission, he came and took the body away.

39 He was accompanied by Nicodemus, the man who earlier had visited Jesus at night. Nicodemus brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about seventy-five pounds.

40 Taking Jesus’ body, the two of them wrapped it, with the spices, in strips of linen. This was in accordance with Jewish burial customs.

41 At the place where Jesus was crucified, there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb, in which no one had ever been laid.

42 Because it was the Jewish day of Preparation and since the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there.

Here, in the most detailed version, Joseph of Arimathea is named as the person who “took the body away”, presumably after having taken it off the cross. Only John says that he was “accompanied by Nicodemus”.

THE DEPOSITION THEME

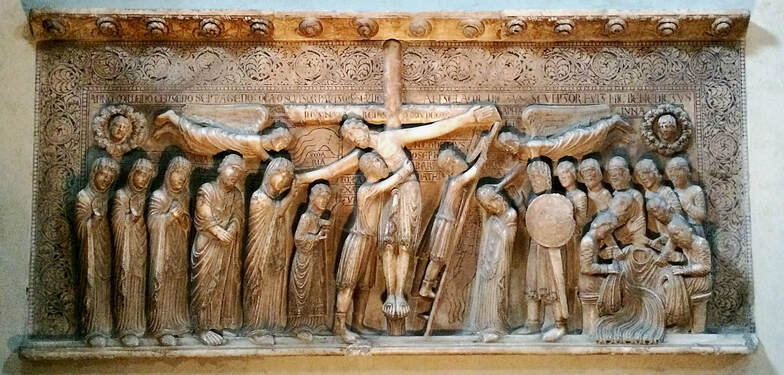

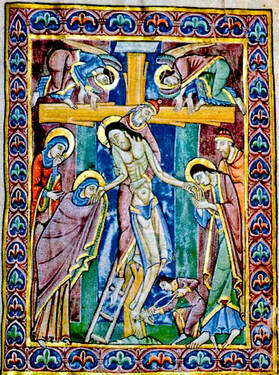

The four medieval images below show different moments in the sequence of the removal of the body of Jesus from the cross, though we see the ladder in all of them. They also are composites of the themes of the Deposition, the Lamentation, and in the fourth image even the Entombment.

Benedetto Antelami Deposition of Christ 1178 marble Parma Cathedral

Here Joseph of Arimathea is shown removing the body of Christ surrounded by mourners on the right of Christ and soldiers on his left. Sometimes, as in this instance, angels were added to the scene – two angels hover above the heads of the standing figures on either side of the cross. The angel above the soldiers seems to be trying to remove the headgear from a short figure. Or did he place it on that person’s head? Is that person another mourner?

Three Depositions

Illuminated Manuscript St. Albans psalter 12th century

Wooden carving 1510-20 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Armenian Illuminated Manuscript 1268 Leningrad

Illuminated Manuscript St. Albans psalter 12th century

Wooden carving 1510-20 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Armenian Illuminated Manuscript 1268 Leningrad

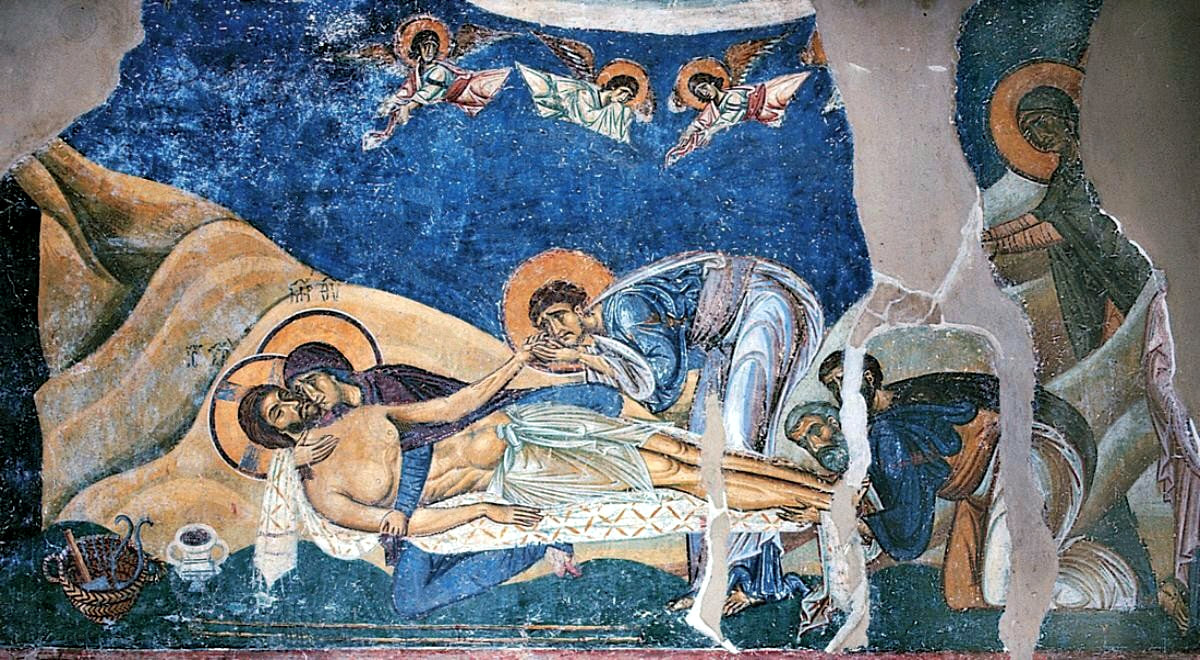

THE LAMENTATION THEME

Once the body of Jesus was removed from the cross it was usually shown in a prone position, held and mourned over by the women who were said to be present: usually the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene, along with others. Over time artists added several more figures in this group, a scene that came to be known as the Lamentation of Christ.

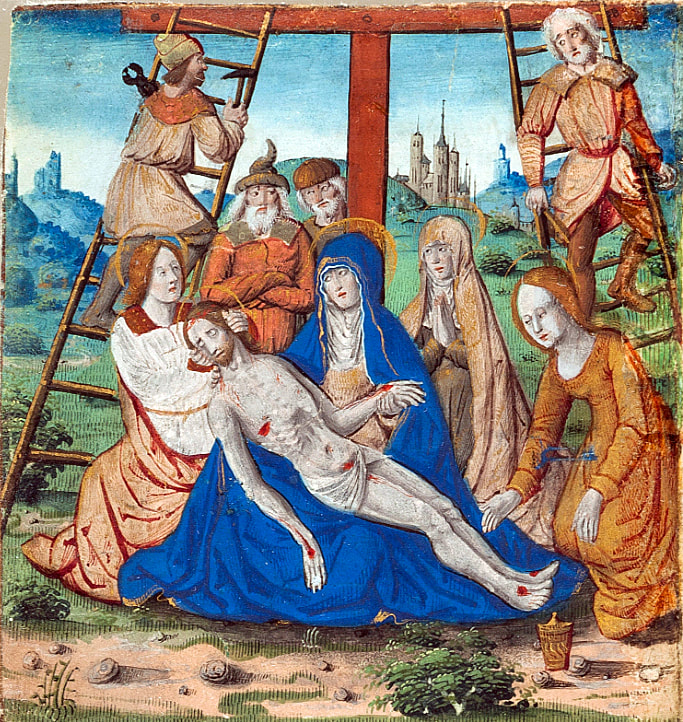

THE PIETÀ THEME

In time one figure – Mary, the mother of Jesus – emerged as the central mourner on the group. She was shown holding her dead son on her lap, an echo of the iconic image of the Mother and Child. It was the image of Mary with the body of her son on her knees that became known as the Pièta.

Two Lamentations

Enguerrand Quarton, Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon 1453-1454 Louvre Museum, Paris

Miniature from a Northern French Book of Hours 1480

These two paintings focus on the central triangular composition of Mary and Jesus,

but the two figures are not isolated as they would be in a Pietà.

Enguerrand Quarton, Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon 1453-1454 Louvre Museum, Paris

Miniature from a Northern French Book of Hours 1480

These two paintings focus on the central triangular composition of Mary and Jesus,

but the two figures are not isolated as they would be in a Pietà.

The dead Christ is shown on the lap of his mother Mary, who is incongruously shown to be no older than her son, a common feature in these Lamentation images, and in those of the Pietà. Indeed the Virgin Mary is almost never shown as an old or even middle-aged woman, not even in images depicting her death.

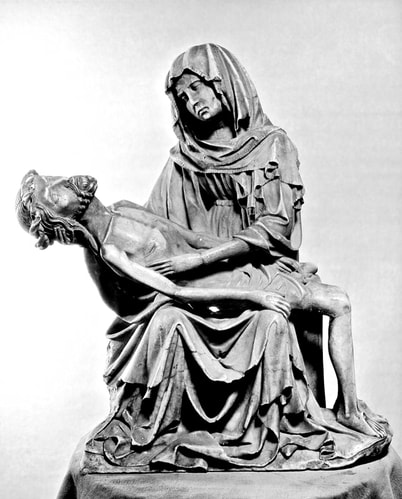

These early and later medieval woodcarvings of the Pietà image show only the two figures of Mary and her dead son. Though in both sculptures the Christ figure is shown as a bearded adult, in the first one his size is that of a child in comparison to his mother, reminiscent of the theme of Mother and Child. The later rendering shows two adults of equal size.

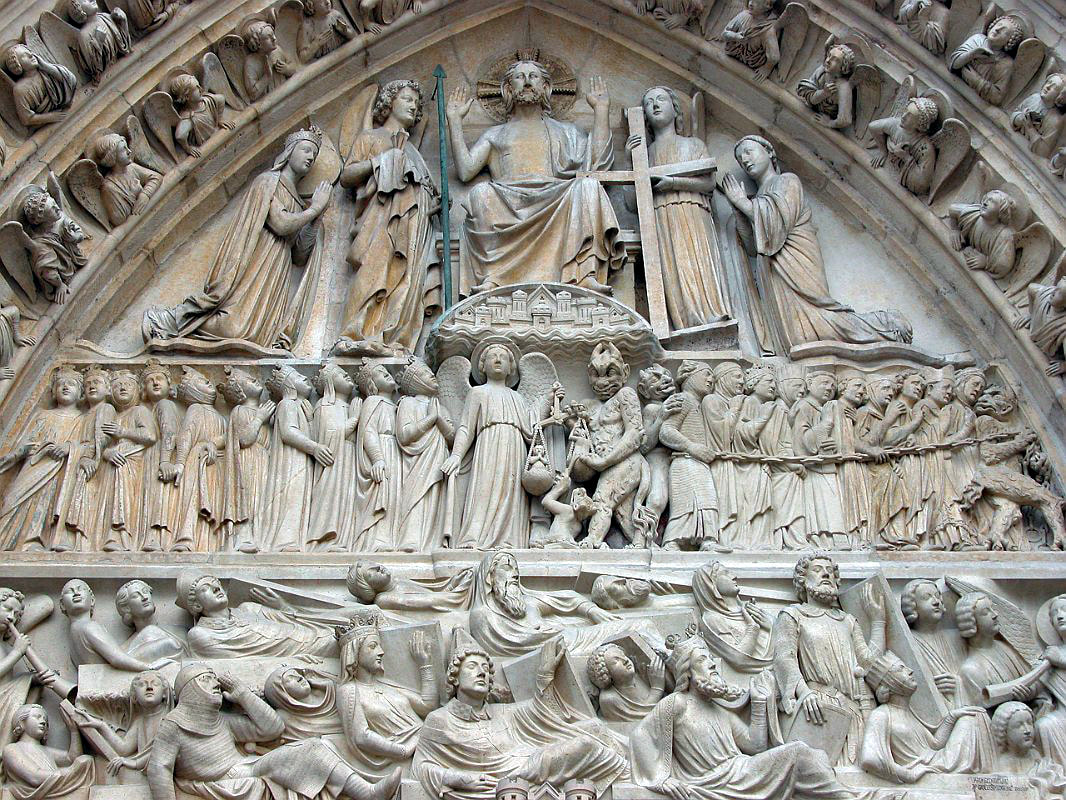

In a Pietà Christ is always shown with his head to the right side of the Virgin Mary, as it was in Michelangelo’s early Pietà. In Christian iconography, being on the right side indicates salvation as shown in all Last Judgments.(right = just, fair, proper, good, upright, righteous, virtuous, etc.)

The Last Judgment above the central portal of Norte Dame, Paris 1220s-1230s

Below the right side of Christ is an angel with the saved; below his left side is the devil with the damned.

Below the right side of Christ is an angel with the saved; below his left side is the devil with the damned.

BACK TO MICHELANGELO'S PIETA

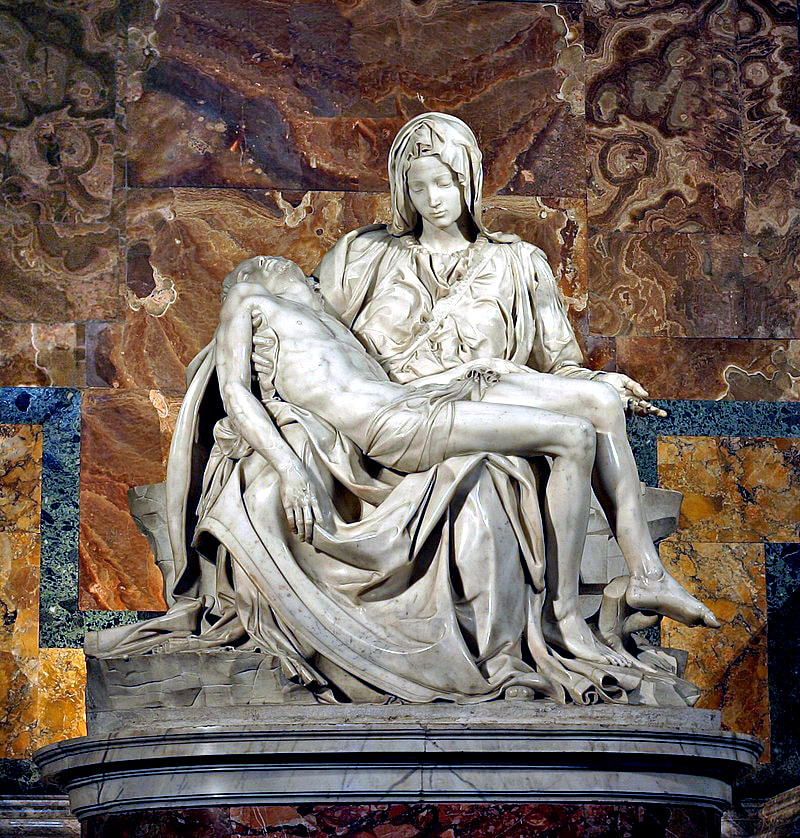

Michelangelo’s first Pietà, now in the Vatican, was commissioned by the French ambassador to the papacy, Cardinal Jean de Bilhères-Lagraulas, and completed in 1498 when Michelangelo was 24.

|

Michelangelo Pietá 1498 marble

|

Pietá c.1420 wood Austrian

|

Though Michelangelo was familiar, through his patrons the Medici, with a great many classical artworks, he may not have known of the works in the northern parts of Europe, like the Austrian piece above that looks so much like his own composition. The Pietá was a well-known theme by the end of the 15th century, and while Michelangelo’s sculpture was within the tradition, the innovations and quality of his treatment were different enough to gain him immediate stature and renown as a preeminent master, a position that he never relinquished.

The much smaller Austrian woodcarving has a similar composition to Michelangelo’s large marble statue, and the figures are shown at similar ages. But the similarities stop there. The older work is colored as were many medieval sculptures, while Michelangelo retains the color of the white Carrara marble in keeping with the ancient Greek and Roman sculptures so honored by his Italian compatriots. His representation and modeling is naturalistic at every level, from the faces to the bodies to the folds of the fabrics.

Yet this naturalism is really an illusion. Although their heads are at the same scale, if the Virgin stood up she would appear nearly twice as tall as the figure of her son, if he stood up instead of lying draped upon her immense lap. This discrepancy is made evident in a comparison with the two Austrian figures, which are of equal stature, with the Jesus figure extended far to the right of the Virgin who must support his head with her extended hand to keep it from falling.

In much of his work Michelangelo worked this illusion of representation within the style of naturalism, usually having the change of scale or proportion express an idea beyond simple representation.

The much smaller Austrian woodcarving has a similar composition to Michelangelo’s large marble statue, and the figures are shown at similar ages. But the similarities stop there. The older work is colored as were many medieval sculptures, while Michelangelo retains the color of the white Carrara marble in keeping with the ancient Greek and Roman sculptures so honored by his Italian compatriots. His representation and modeling is naturalistic at every level, from the faces to the bodies to the folds of the fabrics.

Yet this naturalism is really an illusion. Although their heads are at the same scale, if the Virgin stood up she would appear nearly twice as tall as the figure of her son, if he stood up instead of lying draped upon her immense lap. This discrepancy is made evident in a comparison with the two Austrian figures, which are of equal stature, with the Jesus figure extended far to the right of the Virgin who must support his head with her extended hand to keep it from falling.

In much of his work Michelangelo worked this illusion of representation within the style of naturalism, usually having the change of scale or proportion express an idea beyond simple representation.

David 1501-1504 Florence

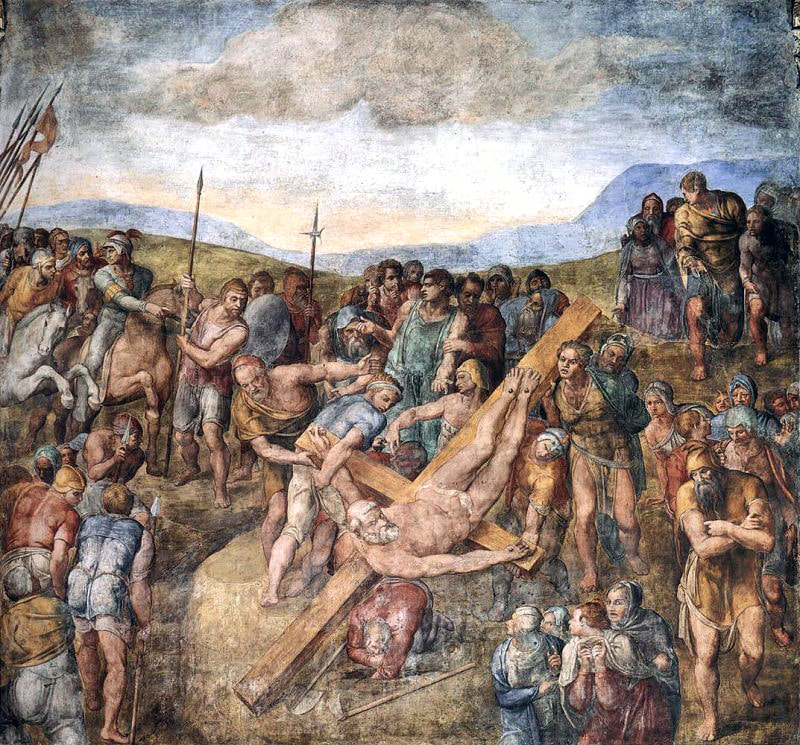

Crucifixion of St. Peter 1546-1550 Vatican

David’s head and hands are oversized compared to the proportions of his body.

St. Peter is gigantic compared to the soldiers and onlookers surrounding him.

Crucifixion of St. Peter 1546-1550 Vatican

David’s head and hands are oversized compared to the proportions of his body.

St. Peter is gigantic compared to the soldiers and onlookers surrounding him.

WORKING FOR HIMSELF

Although most of Michelangelo’s sculpture, painting, and architecture were commissioned works, in his last years he made two major sculptures just for himself. In 1547, at the age of 72, he began to work on what has come to be known as The Deposition (Pietá Bandini), intending it to be, according to Vasari, for his own tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (the Deposition is now in Florence).

Bandini Deposition (1547-1555) 89-in. tall Cathedral Museum, Florence

Without commenting on its composition and meaning, I mention this work because it has a direct bearing on the Rondanini Pietá in a special way. After working on this Deposition for eight years, on a night in 1555 – according to contemporary commentary – Michelangelo mutilated the sculpture for reasons still unknown. He broke off several limbs, including the arms and left leg of the Christ figure and completely abandoned the sculpture, giving it to one of his servants. Eventually the piece was sold to the Archbishop of Siena, Francesco Bandini (thus the name Pietà Bandini), who had a young sculptor restore the work, reattaching broken off limbs, hands and fingers – all but the left leg of Christ.

Image showing the Deposition’s broken-off limbs that were later re-attached.

THE RONDANINI PIETÀ

The Pietà now in the Sforza Castle in Milan is called the Rondanini Pietá because it stood for centuries in the courtyard of the Palazzo Rondanini in Rome.

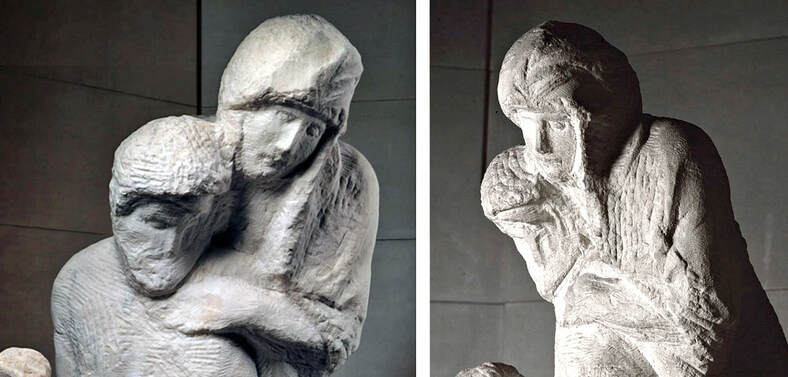

Rondanini Pietà

The Pietà was mounted on a Roman marble altar as a pedestal.

Today it stands on a modern pedestal, installed in a special gallery in the Sforza Castle.

The Pietà was mounted on a Roman marble altar as a pedestal.

Today it stands on a modern pedestal, installed in a special gallery in the Sforza Castle.

Michelangelo worked on the Rondanini Pietà in two stages: between 1552 and 1553, while still working on the Deposition (1547-1555), and later, after he destroyed the Deposition, from 1555 to 1564.

The sculpture, as Michelangelo left it at his death in 1564, is a composite of two distinct renderings coexisting in an interrupted moment of metamorphosis. Christ’s legs and the fragment of his right arm are modeled in the manner of the damaged Deposition, depicting the flesh of the body with a smooth finish to the marble. If there was a first version of the piece, as noted by Vasari and other contemporary writers, it probably looked close to the style of the Christ in the Deposition, anatomically naturalistic.

I tried to envision what that first rendering may have looked like by overlaying a modified version of the upper body of the Deposition Christ onto the Rondanini figure. Of course this is only a crude guess, but this rendering of the figure would have allowed Michelangelo to cut away the finished carving to the core of the torso of the final sculpture.

The sculpture, as Michelangelo left it at his death in 1564, is a composite of two distinct renderings coexisting in an interrupted moment of metamorphosis. Christ’s legs and the fragment of his right arm are modeled in the manner of the damaged Deposition, depicting the flesh of the body with a smooth finish to the marble. If there was a first version of the piece, as noted by Vasari and other contemporary writers, it probably looked close to the style of the Christ in the Deposition, anatomically naturalistic.

I tried to envision what that first rendering may have looked like by overlaying a modified version of the upper body of the Deposition Christ onto the Rondanini figure. Of course this is only a crude guess, but this rendering of the figure would have allowed Michelangelo to cut away the finished carving to the core of the torso of the final sculpture.

The Bandini Deposition

My speculative composite

The Rondanini Pietà

My speculative composite

The Rondanini Pietà

I projected the upper torso and head and the left arm of the Deposition’s Christ (in blue) onto the Pietà to match the still existing legs and right arm of the figure of Jesus. In the final sculpture of the Pietà, the left arm of the first version is gone, the right arm is retained, and the torso has been reduced to the rough and narrow version that Michelangelo left when he died. The head, which was probably similar to the one in the Deposition (as shown in blue), has also been reduced to the rough and indistinct face we see now.

Whatever shape the second figure was originally, it has been carved away and formed into the person now seen above and behind Jesus. It may have been a version of the bearded figure behind Christ in the Deposition, with the four-figure composition having been reduced to the central two figures. Michelangelo’s first version would likely have shown the second figure in a style similar to the Christ figure, it’s head and body more naturalistic and smoothly finished.

This may have been where Michelangelo stopped working on this piece in 1553, at the end of the first stage of working on it as understood by researchers.

He continued work on his Deposition, but in 1555 he suddenly dismembered and abandoned that work. He was 80 years old, and he returned to work on the Pietá. Then at some point he again found himself dissatisfied, but instead of mutilating it and giving up on the piece, as he did with the Deposition, he worked on transforming it into a different vision for nearly nine years.

In paintings, when dissatisfied with the progress of a work, an artist can paint over some area to change a detail or even a large section of a composition. When parts of the earlier versions are still apparent in the final work, they are called pentimenti, an Italian word for repentance.

But in stone carving, whatever is changed in the sculpture is lost, since all changes are made by subtraction, by the removal of stone. So it was a serious act of courage for Michelangelo, probably in his mid-eighties, to break off large finished sections of his last work in progress because his ideas and intentions for the sculpture had changed.

The Rondanini Pietà, which had stunned me in Milan in 1962, seems to exist simultaneously in different times and embodiments, and on various levels of meaning. The treatment of Christ’s legs and the still-retained but detached right arm refer to the great influence on the Renaissance of classical Greek and Roman sculpture, while Christ’s head and the figure of Mary, roughly hewn, suggest the elongated figures on Gothic cathedrals.

Whatever shape the second figure was originally, it has been carved away and formed into the person now seen above and behind Jesus. It may have been a version of the bearded figure behind Christ in the Deposition, with the four-figure composition having been reduced to the central two figures. Michelangelo’s first version would likely have shown the second figure in a style similar to the Christ figure, it’s head and body more naturalistic and smoothly finished.

This may have been where Michelangelo stopped working on this piece in 1553, at the end of the first stage of working on it as understood by researchers.

He continued work on his Deposition, but in 1555 he suddenly dismembered and abandoned that work. He was 80 years old, and he returned to work on the Pietá. Then at some point he again found himself dissatisfied, but instead of mutilating it and giving up on the piece, as he did with the Deposition, he worked on transforming it into a different vision for nearly nine years.

In paintings, when dissatisfied with the progress of a work, an artist can paint over some area to change a detail or even a large section of a composition. When parts of the earlier versions are still apparent in the final work, they are called pentimenti, an Italian word for repentance.

But in stone carving, whatever is changed in the sculpture is lost, since all changes are made by subtraction, by the removal of stone. So it was a serious act of courage for Michelangelo, probably in his mid-eighties, to break off large finished sections of his last work in progress because his ideas and intentions for the sculpture had changed.

The Rondanini Pietà, which had stunned me in Milan in 1962, seems to exist simultaneously in different times and embodiments, and on various levels of meaning. The treatment of Christ’s legs and the still-retained but detached right arm refer to the great influence on the Renaissance of classical Greek and Roman sculpture, while Christ’s head and the figure of Mary, roughly hewn, suggest the elongated figures on Gothic cathedrals.

These details show the difference in finish of the earlier legs and the later upper body of Christ.

In this final work, the aged Michelangelo seems to have repudiated the Renaissance focus on corporeal reality, on accurate anatomy and the classical fluidity of postures. Here he created an exceptional image of the Pietá that is vertical and columnar instead of grounded in the triangular composition of the seated Mary holding Christ on her lap.

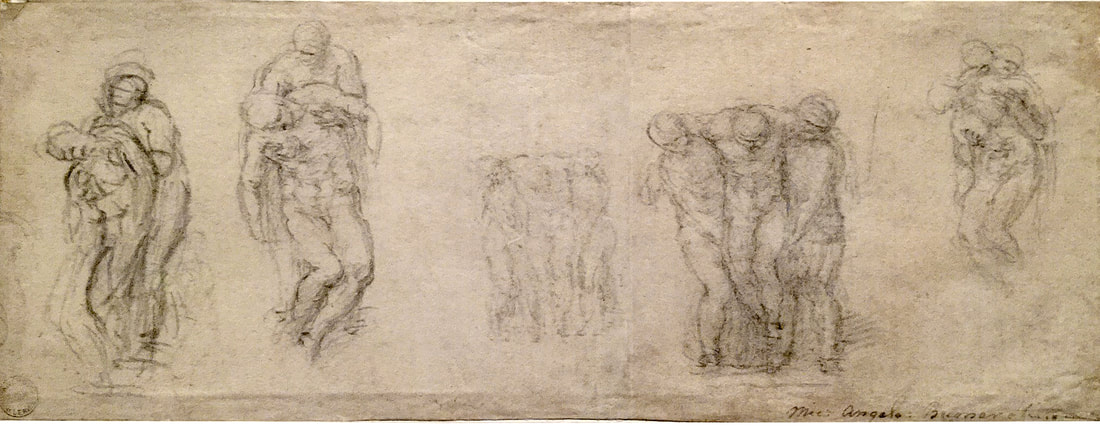

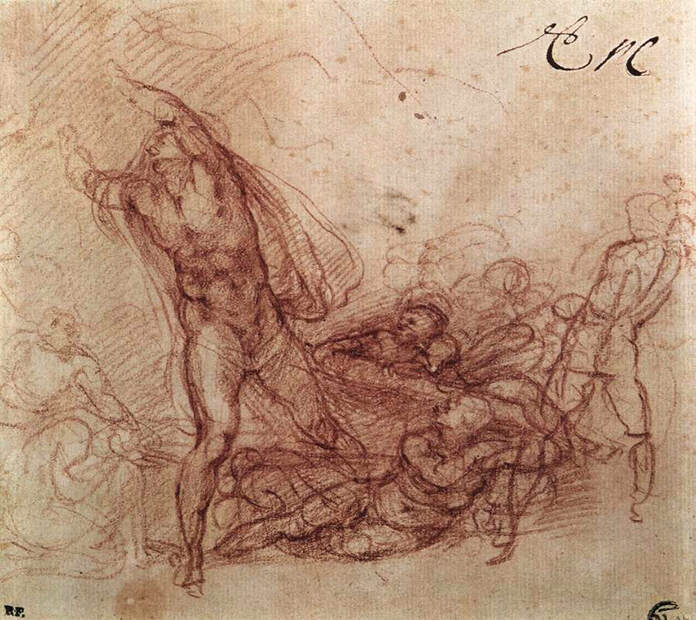

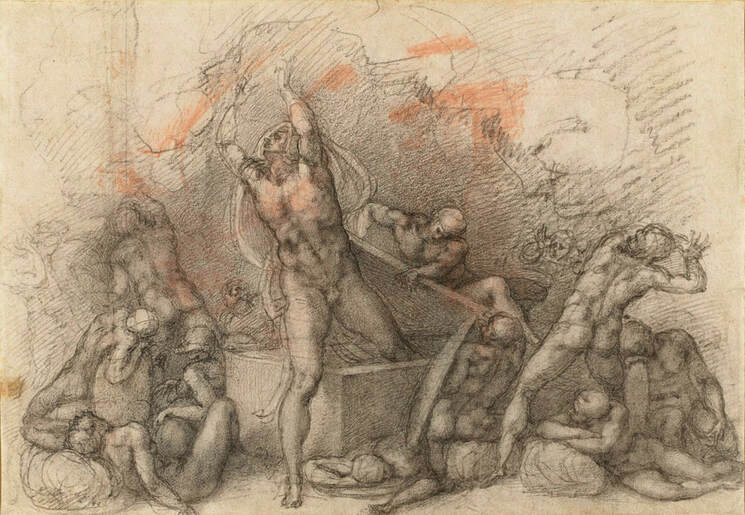

Indeed the Rondanini Pietá seems more related in composition to a Deposition in its vertical structure, although with a major difference. Unlike in the two drawings below that Michelangelo drew at the time he was working on the Pietá, where the weighty dead body of Christ is being supported by a sturdy figure as it is removed from the cross, the Christ of the sculpture is slight and upright, and his torso is not sagging. His head is not falling, but inclined and leaning on Mary.

Indeed the Rondanini Pietá seems more related in composition to a Deposition in its vertical structure, although with a major difference. Unlike in the two drawings below that Michelangelo drew at the time he was working on the Pietá, where the weighty dead body of Christ is being supported by a sturdy figure as it is removed from the cross, the Christ of the sculpture is slight and upright, and his torso is not sagging. His head is not falling, but inclined and leaning on Mary.

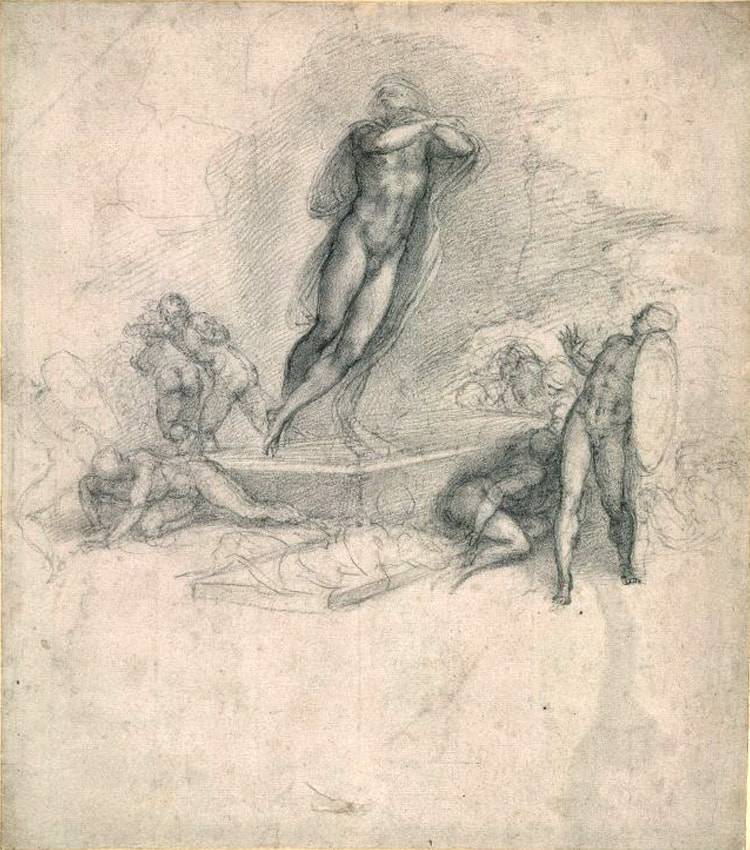

A sheet of several drawings c.1555 black chalk Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England

Detail Two studies, possibly for a Deposition or Entombment

In these drawings the figure behind Christ is obviously supporting an inert and limp body, a large sagging weight that takes some strength to support. The drawing on the left is especially similar in position to the two figures in the Pietá. These drawings may be either studies for a Deposition or an Entombment; there is a wide range of expert opinion on the purpose and dating of these drawings.

But the Pietá is a drastically different composition. The figure behind Christ is no longer a strong male, capable of supporting a dead body, but a female, possibly the Virgin Mary.

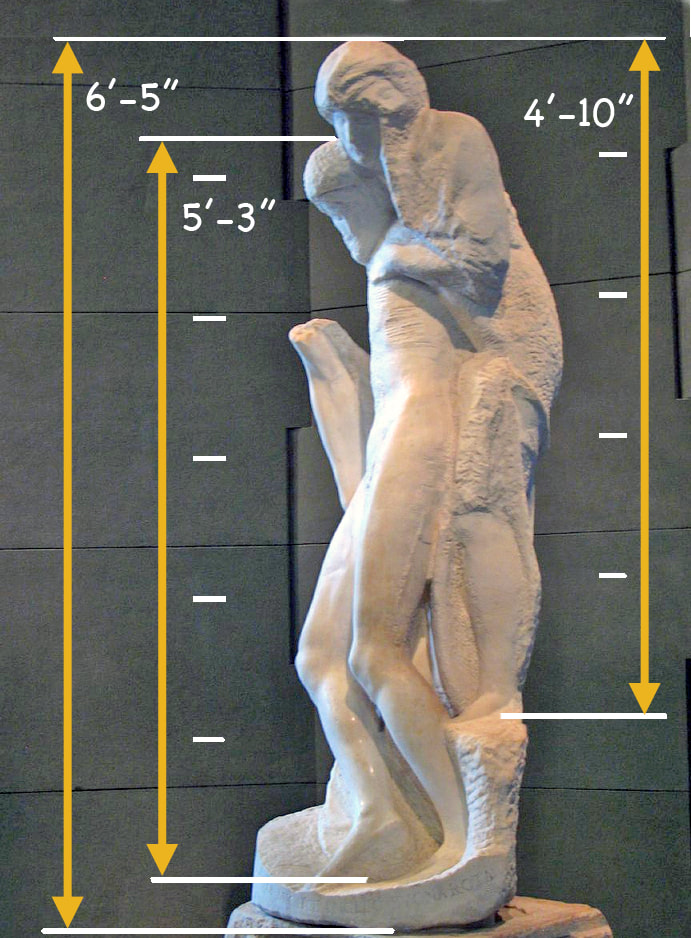

The figures are approximately life size. The full sculpture measures 77 inches in height, or 6-ft. 5-in. tall. Working from a photograph I estimated the heights of the two figures here:

But the Pietá is a drastically different composition. The figure behind Christ is no longer a strong male, capable of supporting a dead body, but a female, possibly the Virgin Mary.

The figures are approximately life size. The full sculpture measures 77 inches in height, or 6-ft. 5-in. tall. Working from a photograph I estimated the heights of the two figures here:

Even adding about 4” to each of the figures, since Christ’s legs are bent and Mary leans forward, we have the full figure of Christ at 5’-7” and Mary at 5’-2” tall. We are told that Michelangelo was of short stature, and by his eighties he may have been even smaller than the Christ in this sculpture. If he stood at the same level as his final work, he may have seen the two faces looking down at him.

As to the interaction of the figures, which seem almost to be fused together, it appears as if Christ is actually supporting Mary rather than the other way around. His body seems to lean backwards, into her forward-leaning upper body resting on his; her chin rests on his head. Their intimacy is palpable.

The two faces are barely differentiated; they are more like sketches than fully realized portraits. It is as if the features are out of focus, especially in contrast to the clarity of the legs and the detached right arm of Christ. The same goes for Christ’s upper torso. His hands are hidden and his arms barely suggested as they hold onto Mary’s body behind him. Her arms and hands are evident, but roughly finished, again more suggested than realistically depicted.

There is an anomaly in the head of Mary, if it is Mary: she has two faces, one looking down, toward her son, the other, a partial face, looking up and away, which is not seen from even the side view unless specially lit.

As to the interaction of the figures, which seem almost to be fused together, it appears as if Christ is actually supporting Mary rather than the other way around. His body seems to lean backwards, into her forward-leaning upper body resting on his; her chin rests on his head. Their intimacy is palpable.

The two faces are barely differentiated; they are more like sketches than fully realized portraits. It is as if the features are out of focus, especially in contrast to the clarity of the legs and the detached right arm of Christ. The same goes for Christ’s upper torso. His hands are hidden and his arms barely suggested as they hold onto Mary’s body behind him. Her arms and hands are evident, but roughly finished, again more suggested than realistically depicted.

There is an anomaly in the head of Mary, if it is Mary: she has two faces, one looking down, toward her son, the other, a partial face, looking up and away, which is not seen from even the side view unless specially lit.

The detail on the left shows the remaining part of the earlier version of the face of Mary,

looking upward (1). The final version (2) was carved out from the lower part of the original head.

looking upward (1). The final version (2) was carved out from the lower part of the original head.

The view from the right side of the sculpture (the left side of the two figures) shows that Mary is standing on a raised platform of stone behind her son, leaning forward onto his shoulders as she holds him close, their heads touching more in a gesture of embrace than of her bearing his dead weight. But there is also an anomaly in her stance, or rather in the depiction of her stance. All depictions of the Virgin Mary, indeed of all women in the Christian narrative up to this time, are shown with full-length garments reaching the ground. In no instance is the Virgin’s leg shown bare. But here, her left leg is bare below the knee. Was this initially a male figure, as in the drawing?

The left and center images show the bare left leg of Mary as she stands on the raised

stone platform behind Christ’s figure. The center and right images show Christ’s arms

reaching back to hold the body of Mary behind him. They also show the earlier right arm.

stone platform behind Christ’s figure. The center and right images show Christ’s arms

reaching back to hold the body of Mary behind him. They also show the earlier right arm.

From both the right and left side views, Christ’s arm reaches behind to grasp Mary; not the gesture of a dead man. Only his bent knees, in the typical gesture in Depositions, indicate that he is not fully planted on the ground. His left foot is grounded but only the toes of his right foot touch the ground, which from this angle (though not from the front) looks like he is stepping forward. He may also be seen as trying to keep his balance as he leans against Mary.

This is not a figure of a corpse sinking and surrendering to the pull of gravity, as is the heavy body of the Christ in the Deposition. This is a lean figure that seems to be rising, nearly floating.

Rejecting the robust and muscular style of his earlier renderings of heroic, mostly male figures, near the end of his life Michelangelo hacked away at the figures of his first version of his last Pietá to reveal a stripped down essence of human form: something else; something new. Compared to the finely shaped and finished lower part of the figure of Christ, his torso and head are more like a suggestion of human form, an emanation.

In reworking the Rondanini Pieta, Michelangelo reversed his usual process. He was known to have said that he carves away the stone to reveal the body inside it: “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.” But here, he removed the sculpted flesh of the upper body of Christ to reveal the rough stone that he fashioned into the less finished body of the final figure.

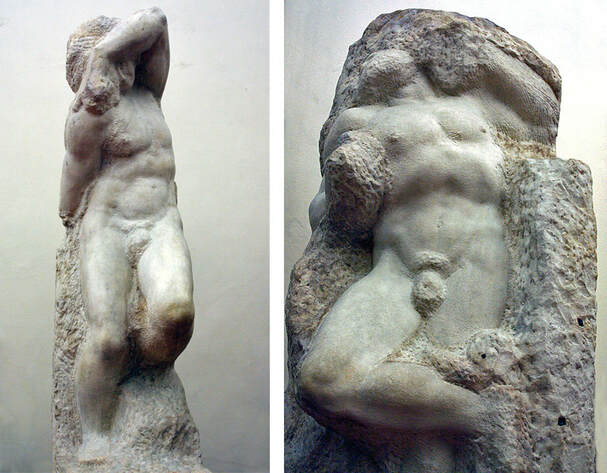

Indeed the sculptures he made between 1520 and 1534 for the uncompleted tomb of Pope Julius, which came to be known as Slaves or Prisoners, provide evidence of this process. Michelangelo stopped removing the stone from the initial blocks at different stages, before revealing the entire figures. These heavy-limbed men seem trapped within the rough-hewn stones struggling to emerge; they attain the visual representations of the essence of struggle, of effort and of conflict.

This is not a figure of a corpse sinking and surrendering to the pull of gravity, as is the heavy body of the Christ in the Deposition. This is a lean figure that seems to be rising, nearly floating.

Rejecting the robust and muscular style of his earlier renderings of heroic, mostly male figures, near the end of his life Michelangelo hacked away at the figures of his first version of his last Pietá to reveal a stripped down essence of human form: something else; something new. Compared to the finely shaped and finished lower part of the figure of Christ, his torso and head are more like a suggestion of human form, an emanation.

In reworking the Rondanini Pieta, Michelangelo reversed his usual process. He was known to have said that he carves away the stone to reveal the body inside it: “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.” But here, he removed the sculpted flesh of the upper body of Christ to reveal the rough stone that he fashioned into the less finished body of the final figure.

Indeed the sculptures he made between 1520 and 1534 for the uncompleted tomb of Pope Julius, which came to be known as Slaves or Prisoners, provide evidence of this process. Michelangelo stopped removing the stone from the initial blocks at different stages, before revealing the entire figures. These heavy-limbed men seem trapped within the rough-hewn stones struggling to emerge; they attain the visual representations of the essence of struggle, of effort and of conflict.

Two of the Slaves or Prisoners marble 1505-1508

Accademia Gallery in Florence

Accademia Gallery in Florence

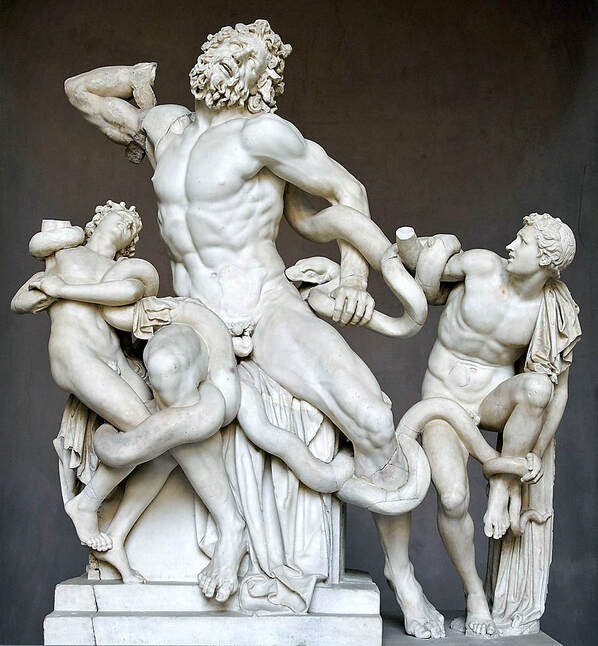

Unlike his possible model, the ancient Greek sculpture of Laocoön and his Sons, Michelangelo stripped conflict of its narrative context and concentrated it within an individual figure, making his Prisoners the representations of a person’s internal struggle.

Laocoön and his Sons marble Vatican Museum

When the sculpture was discovered in 1506, buried in a vineyard in Rome,

Michelangelo was one of the first to be called to the excavation site.

When the sculpture was discovered in 1506, buried in a vineyard in Rome,

Michelangelo was one of the first to be called to the excavation site.

Perhaps more than any other artist of the Renaissance, Michelangelo spanned the range between the perennial polarities: serenity, calm, and peace, vs. struggle, conflict, and violence. His early work, influenced by the serenity and equipoise of ancient Greek sculptures and their ideal of physical beauty, emphasized figures in repose, such as the early Pietá and the heroic David, made in his twenties. In contrast, in his sixties he painted the immense Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, creating a vast scope of figures in struggle and desperation, with a gigantic Christ in a gesture of condemnation of the sinners on his left side. He created a scene, or more accurately multiple scenes, of turmoil and exaggerated actions, even among the saved.

Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, the Vatican 1536 to 1541

Michelangelo was criticized at the time for his nude bodies, some of which were “clothed” – painted over – after his death, and for the beardless face of Christ, a youthful and powerful Apollonic figure, more classical and “pagan” than Christian.

Detail showing Christ the Judge

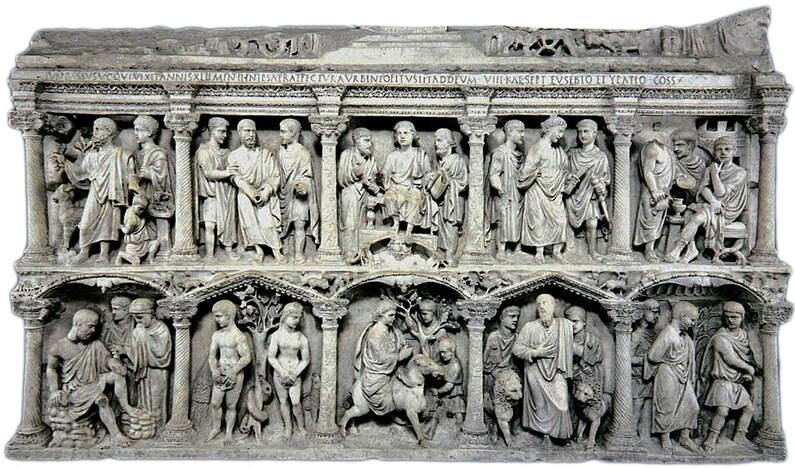

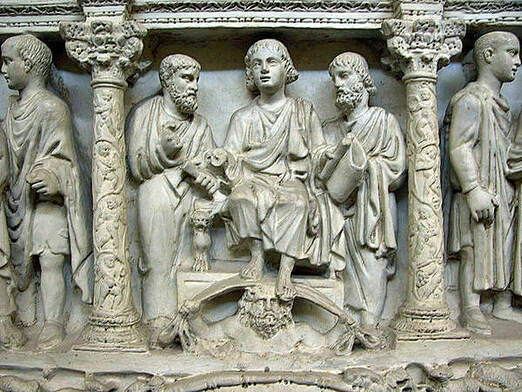

The depiction of Jesus evolved throughout the history of the church. Some of the earliest portrayals are on the sarcophagi of Roman Christians.

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus 4th century

Detail of Jesus with two apostles

5th century Christian casket ivory

In these early Christian sculptures a young and beardless Jesus is shown, carved in the style of the classical figures of Roman art.

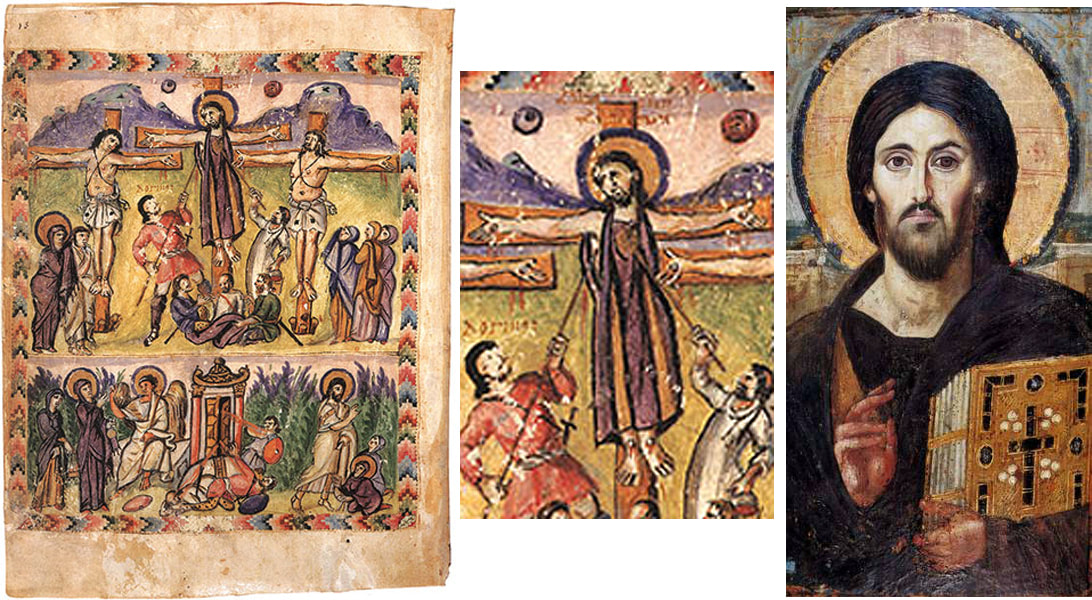

Later, in the early middle ages, Jesus was given a beard, a depiction that has persisted for the ensuing centuries.

Later, in the early middle ages, Jesus was given a beard, a depiction that has persisted for the ensuing centuries.

Page from the Rabbula Gospels Byzantine 6th century, Laurentian Library, Florence

Christ Pantocrator (ruler of the universe) Byzantine 6th century, St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai

Christ Pantocrator (ruler of the universe) Byzantine 6th century, St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai

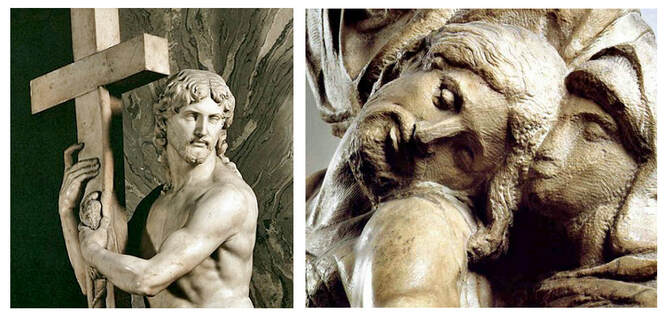

In his first Pietá, Michelangelo gave his Christ long hair and a slight beard on his chin, barely visible on his otherwise clean youthful face, similar to the depiction in his painting of the Entombment two years later.

Details of Michelangelo’s treatment of Christ’s beard in four works.

Pietá 1498

Entombment c.1500

Entombment c.1500

Risen Christ 1521

Deposition 1555

Deposition 1555

In his later sculptures Christ is still shown with a beard on his chin, but slightly more pronounced. Of his completed works only the Christ in the Last Judgment on the great wall of the Sistine Chapel is clean-shaven, though in later years Michelangelo made several drawings of the beardless Christ risen from his tomb.

The Christ of the Rondanini Pietá is fully bearded, as much as we can tell from the rough carving. There is a slight indication of the lower edge of the mustache, but the beard obscures the mouth. Christ’s hair seems more like a cap, a simple mass, in contrast to earlier depictions by Michelangelo. In a way it echoes the rounded head covering of Mary.

The Christ of the Rondanini Pietá is fully bearded, as much as we can tell from the rough carving. There is a slight indication of the lower edge of the mustache, but the beard obscures the mouth. Christ’s hair seems more like a cap, a simple mass, in contrast to earlier depictions by Michelangelo. In a way it echoes the rounded head covering of Mary.

These details show Christ’s full beard, barely distinguished from his face,

though clearly elongating it and emphasizing its downward gesture.

though clearly elongating it and emphasizing its downward gesture.

The melding of the beard with the face is part of the softening, almost an erasing of details that characterizes the upper part of the sculpture.

We may assume that this upper part is the area that Michelangelo worked on after he cut away his earlier renderings of the figures. Since we have no record of what the sculpture looked like before his drastic removal of a large amount of the already carved stone, we can only guess at the lost sculpture from the lower body of the Christ figure and the lower part of the right arm still attached to the sculpture.

Why were these parts of the sculpture left unchanged? Did Michelangelo run out of time? It would have taken very little effort to remove the old right arm, since we know that he broke many more limbs off from his earlier Depostition in a single day. While the legs of Christ still work, in a way, with his upper body, that old right arm seems to have no use to the figure at all.

But there may be a reason Michelangelo kept it, an idea based on an earlier Renaissance practice. Many Renaissance painters based the renderings of figures on the classic models of Greek and Roman sculptures. However in their religious works they often included aspects of the classical world as a reminder of what Christianity had replaced with a higher aspiration for life and the afterlife. These reminders often took the form of classical architecture, sometimes seen as ruins, within the narrative paintings of the Nativity or the Adoration.

Here are two paintings of the Adoration: one is by Sandro Boticelli (1145-1510), whose frescos in the Sistine Chapel were completed in 1482, twenty six years before Michelangelo began work on the Sistine ceiling, the other is by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494). In both of these Adorations we can see the relics of the architecture of the ancient classical age functioning as backdrops to a scene illustrating the nominal start of the Christian era; the new age replacing the ruins of the old.

We may assume that this upper part is the area that Michelangelo worked on after he cut away his earlier renderings of the figures. Since we have no record of what the sculpture looked like before his drastic removal of a large amount of the already carved stone, we can only guess at the lost sculpture from the lower body of the Christ figure and the lower part of the right arm still attached to the sculpture.

Why were these parts of the sculpture left unchanged? Did Michelangelo run out of time? It would have taken very little effort to remove the old right arm, since we know that he broke many more limbs off from his earlier Depostition in a single day. While the legs of Christ still work, in a way, with his upper body, that old right arm seems to have no use to the figure at all.

But there may be a reason Michelangelo kept it, an idea based on an earlier Renaissance practice. Many Renaissance painters based the renderings of figures on the classic models of Greek and Roman sculptures. However in their religious works they often included aspects of the classical world as a reminder of what Christianity had replaced with a higher aspiration for life and the afterlife. These reminders often took the form of classical architecture, sometimes seen as ruins, within the narrative paintings of the Nativity or the Adoration.

Here are two paintings of the Adoration: one is by Sandro Boticelli (1145-1510), whose frescos in the Sistine Chapel were completed in 1482, twenty six years before Michelangelo began work on the Sistine ceiling, the other is by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494). In both of these Adorations we can see the relics of the architecture of the ancient classical age functioning as backdrops to a scene illustrating the nominal start of the Christian era; the new age replacing the ruins of the old.

Sandro Botticelli Adoration of the Magi 1481-1482 National Galley, Washington

Domenico Ghirlandaio Adoration of the Shepherds 1483-85 Santa Trinita, Florence

The classical sarcophagus in the Ghirlandaio painting is not just a trough for the ox and the ass. It also bears a Latin inscription of an ancient prophecy, translated as: “While Fulvius, augur of Pompey, was felled by the sword in Jerusalem he said: the urn that contains me shall bring forth a god.” Ghirlandaio uses this Roman prophecy to show the baby Jesus replacing all of the classical gods, Christianity replacing the pagan world.

I think that it is possible that in the Rondanini Pietà, Michelangelo kept a similar gesture – the “relic” fragment of his classically formed right arm of Christ – as a reminder of what he was rejecting: the humanistic Renaissance aesthetic of the pagan ancients, the Greek and Roman models, as well as his own heroic Renaissance adaptations of the classics in his great former works.

We know that in his late years Michelangelo was drawn to the religious circle of his friend Vittoria Colonna, a group that sought to reform the Church towards greater spirituality. Following the epoch of spirituality in art of the so-called Middle Ages, the Renaissance artists countered with the worldly naturalism derived from classical sculpture. So it is possible that Michelangelo, in his partial destruction of the classical figures of his last Pietá, strove to reveal a representation closer to the medieval spirit of the Church, of faith rather than rationality.

But more than his effacement of the earlier naturalistic rendering of the upper sections of the two figures, I see in this sculpture Michelangelo’s effort to create a new Christian icon, an image not of death but of resurrection. If the meaning of Christianity lay in the resurrection of Jesus, why did his death by crucifixion become the central image of the Church?

By Michelangelo’s time the Church had long ago abandoned the second Commandment, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any craven image”. Indeed Christian visual arts had become the familiar language of the Church’s teachings for its multitudes of illiterate faithful, as well as the cherished property of the Church itself and its wealthy clerics and patrons.

Renaissance artists were kept busy illustrating the life of Jesus in all its scriptural and apocryphal narrative details. But the central icon of his life had become his death on the cross, and the cycle of the Passion of Christ grown around the Crucifixion.

It has always perplexed me why Christians focused their veneration of their god on his death, a most inglorious death meted out by the Roman powers to low life criminals and enemies of the state: Crucifixion was considered the most horrible, slow, painful, and humiliating form of execution possible, a public spectacle used to frighten and dissuade others from similar acts.

After all, it was not his shameful and agonizing death but what came after that – his rising from the dead – that made the young Jewish rabbi into the Christian messiah. And yet the Resurrection of Jesus received only a small number of visual representations compared to the myriad renderings of the Crucifixion and the ubiquitous emblem of the cross.

But Michelangelo did make a series of drawings of the Resurrection of Jesus, three of which are shown below. It is not known if these were studies for a commissioned project, or made as gifts for friends or patrons.

I think that it is possible that in the Rondanini Pietà, Michelangelo kept a similar gesture – the “relic” fragment of his classically formed right arm of Christ – as a reminder of what he was rejecting: the humanistic Renaissance aesthetic of the pagan ancients, the Greek and Roman models, as well as his own heroic Renaissance adaptations of the classics in his great former works.

We know that in his late years Michelangelo was drawn to the religious circle of his friend Vittoria Colonna, a group that sought to reform the Church towards greater spirituality. Following the epoch of spirituality in art of the so-called Middle Ages, the Renaissance artists countered with the worldly naturalism derived from classical sculpture. So it is possible that Michelangelo, in his partial destruction of the classical figures of his last Pietá, strove to reveal a representation closer to the medieval spirit of the Church, of faith rather than rationality.

But more than his effacement of the earlier naturalistic rendering of the upper sections of the two figures, I see in this sculpture Michelangelo’s effort to create a new Christian icon, an image not of death but of resurrection. If the meaning of Christianity lay in the resurrection of Jesus, why did his death by crucifixion become the central image of the Church?

By Michelangelo’s time the Church had long ago abandoned the second Commandment, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any craven image”. Indeed Christian visual arts had become the familiar language of the Church’s teachings for its multitudes of illiterate faithful, as well as the cherished property of the Church itself and its wealthy clerics and patrons.

Renaissance artists were kept busy illustrating the life of Jesus in all its scriptural and apocryphal narrative details. But the central icon of his life had become his death on the cross, and the cycle of the Passion of Christ grown around the Crucifixion.

It has always perplexed me why Christians focused their veneration of their god on his death, a most inglorious death meted out by the Roman powers to low life criminals and enemies of the state: Crucifixion was considered the most horrible, slow, painful, and humiliating form of execution possible, a public spectacle used to frighten and dissuade others from similar acts.

After all, it was not his shameful and agonizing death but what came after that – his rising from the dead – that made the young Jewish rabbi into the Christian messiah. And yet the Resurrection of Jesus received only a small number of visual representations compared to the myriad renderings of the Crucifixion and the ubiquitous emblem of the cross.

But Michelangelo did make a series of drawings of the Resurrection of Jesus, three of which are shown below. It is not known if these were studies for a commissioned project, or made as gifts for friends or patrons.

Resurrection of Christ c.1530 Louvre Museum, Paris

Red chalk 5.98” x 6.73”

Red chalk 5.98” x 6.73”

Resurrection of Christ 1532 Royal Collection, Windsor

Black chalk over traces of stylus, with some red chalk offsetting 48.82” x 13.66”

Black chalk over traces of stylus, with some red chalk offsetting 48.82” x 13.66”

In these two drawings he was working out an imagined illustration of the dramatic moment when Christ bursts out of his tomb, a scene not described in the Gospels. As in the Last Judgment of the Sistine Chapel that Michelangelo began a few years later, in 1536, Christ is much larger than the other figures – the sleeping soldiers guarding the tomb – and is shown with the heroic classical nude body derived from Greek and Roman sculptures.

With one foot still in the tomb and the other stepping forth onto the ground, Christ’s arms and face are raised as if to heaven, suggesting flight, in contrast to the prone, earthbound bodies of the other figures. The one other standing figure is shown recoiling in fright, in a smaller, countering gesture to that of the risen Christ.

With one foot still in the tomb and the other stepping forth onto the ground, Christ’s arms and face are raised as if to heaven, suggesting flight, in contrast to the prone, earthbound bodies of the other figures. The one other standing figure is shown recoiling in fright, in a smaller, countering gesture to that of the risen Christ.

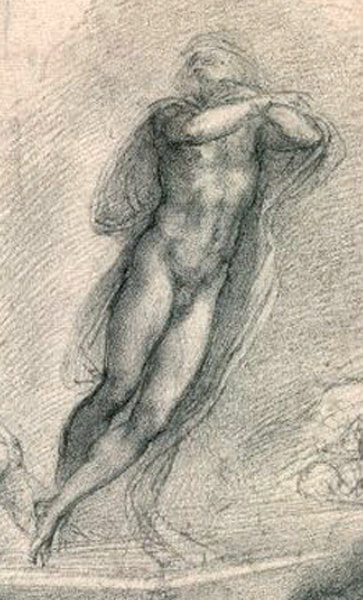

The Resurrection of Christ 1532-33 The British Museum

Black chalk, the point moistened in places to strengthen the outline 12.8” x 11.2"

Black chalk, the point moistened in places to strengthen the outline 12.8” x 11.2"

In this drawing Christ’s arms are in a curious, self-contained gesture shielding his face, not raised as in the other drawings. Is he hiding his face or blocking out the sight of the world? I can’t find a similar gesture in any other images by Michelangelo. His body is rising from the tomb, floating effortlessly, with his feet crossed as if still on the cross, and not touching the ground.

Christ’s body is still much larger than those of the other figures, but it is more isolated and centered than in the two other drawings. He could be shown without the surrounding scene and still be seen as a rising figure (as in the detail).

BACK TO THE RONDANINI PIETÀ

The Rondanini Pietà, however, is not an illustration of an imagined scene. Rather it is a rendering of an idea, a representation of a concept.

Looking back to 1962 in Milan, I think back to the impression of that column of white marble in the light, with the figure rising or suspended above me – a suggestion, an emanation – unlike any other sculpture I had seen before.

Michelangelo always used the human body as a vehicle for his visual ideas. The Rondanini Pietà gives form to the personally sensed contemplation of death of an old man of faith through the depiction of a young man’s body, and it seems to me that in his last sculpture he sought to create not another Pietà, as it has come to be called, but a vital new icon of the Resurrection of Jesus, in his preferred medium, the white marble of Carrara.

Christ’s body is still much larger than those of the other figures, but it is more isolated and centered than in the two other drawings. He could be shown without the surrounding scene and still be seen as a rising figure (as in the detail).

BACK TO THE RONDANINI PIETÀ

The Rondanini Pietà, however, is not an illustration of an imagined scene. Rather it is a rendering of an idea, a representation of a concept.

Looking back to 1962 in Milan, I think back to the impression of that column of white marble in the light, with the figure rising or suspended above me – a suggestion, an emanation – unlike any other sculpture I had seen before.

Michelangelo always used the human body as a vehicle for his visual ideas. The Rondanini Pietà gives form to the personally sensed contemplation of death of an old man of faith through the depiction of a young man’s body, and it seems to me that in his last sculpture he sought to create not another Pietà, as it has come to be called, but a vital new icon of the Resurrection of Jesus, in his preferred medium, the white marble of Carrara.

1. Frontal view and 2. Side view (looking at the right side of the figures

Beyond the details discussed before, I believe that two basic elements of the sculpture justify this idea:

1. The composition:

The overall rising movement of this sculpture is especially evident in the view from the right side of the figures: the limbs (and even the empty spaces between the carved forms) combine to create a visual chord of parallel curves, an upward thrusting arc in what is otherwise a columnar form.

The sculpture as a whole, in all its various elements, rises from the ground of its anchoring base up to the forward-jutting heads poised directly above it.

2. The body:

In destroying the earlier version of the robust finished upper body of Christ, Michelangelo “revealed” a different image – a thinner, rough-hewn and more ephemeral upper body, more frail than heroic, less clearly in focus than the surface of the smooth legs that he retained.

As in aerial perspective in painting, where close objects are shown in clearer detail than distant ones, this body of Christ appears to be rising from the sharply focused details of the lower body toward the less clearly focused surface of the torso and head, suggesting a movement from the space close to the viewer toward a more distant space.

The sculpture appears to be a metamorphosis of the body not only in space (close to far), but also in time (now to then): a visual metaphor for the change from the death of the body in the present to the life of the spirit in the eternal. A Resurrection.

This is a complex piece, a composite of themes of the Deposition, Lamentation, Pietà and Entombment gestures quoted and transformed into something new. It was too enigmatic, idiosyncratic, and personal to become a template for future artists to follow. Because it was left unfinished at the time of his death, this great work by Michelangelo was almost forgotten for centuries.

But what if its contradictions, its fragmentation, and conflicting styles and finish were the essence of the work? What if the meaning of the work was not completion but the process of transformation? A transformation not in the literal sense, but a more essential and imaginative or spiritual metamorphosis, an exceptional old man’s power to shape stone into a form of complex ideas and emotions.

THE HINGE

A hinge is a turning point, a pivot for opening and closing a door, a door between one space and another – in the case of the Rondanini Pietà, between one mode of thinking and another. Michelangelo closes the classical vocabulary of his whole career and opens the possibility for a new visual language in the quest to understand the human condition.

His last sculpture embodies not just conflict, which he had developed in a great number of figures both in sculpture and painting, but something more abstract – irresolution, the visual realization of “not knowing”. While Christian faith calls for trust in dogma and the rejection of doubt, this work is the manifestation of quest, of search, of uncertainty.

This is a work in a new, modern spirit. Not Christian certainty and doctrine or classical Platonic rationality and measured coherence, but inconsistency, fragmentation, the transitional and conditional perception of meanings within any proposition. Not knowing.

What is life? What is death? Fighting against the limited time and strength left to him, the aged Michelangelo struggled physically and mentally to convey this insight of complexity and indeterminacy using his preferred medium – the obdurate material of stone.

This is part of the testament of the Rondanini Pietà, at least as far as I have been able to reflect on it. Barely commented on at Michelangelo’s death, it has been preserved long enough to emerge as one of the most significant artworks we have from his or any other hand.

There were no immediate heirs to this radical work by Michelangelo. Not in the following periods of Italian art, in the Mannerist or Baroque or Rococo periods, which, while pushing the naturalistic underpinnings of the Renaissance with elaborated figurative depiction and vivid details, did not break with naturalism. The heirs I think of were artists who tried to take figurative art beyond illustration to some intangible and concealed levels of meaning, which in the modern period came to be called expressionism.

One post-Renaissance painter that comes to mind is El Greco, an artist concerned with the spiritual meaning of life who contrived idiosyncratic figures to depict mysteries, the strange.

The true heirs of the Rondanini Pietà came much later, in the modern era. I think of how these painters depicted the human image: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Soutine, Kokochka, Chagall, Klee, Matisse in some works, Francis Bacon, and of course Picasso. Especially Picasso. And in sculpture: some works by Rodin, like his Balzac, Giacometti, Henry Moore, and again Picasso. Especially Picasso.

1. The composition:

The overall rising movement of this sculpture is especially evident in the view from the right side of the figures: the limbs (and even the empty spaces between the carved forms) combine to create a visual chord of parallel curves, an upward thrusting arc in what is otherwise a columnar form.

The sculpture as a whole, in all its various elements, rises from the ground of its anchoring base up to the forward-jutting heads poised directly above it.

2. The body:

In destroying the earlier version of the robust finished upper body of Christ, Michelangelo “revealed” a different image – a thinner, rough-hewn and more ephemeral upper body, more frail than heroic, less clearly in focus than the surface of the smooth legs that he retained.

As in aerial perspective in painting, where close objects are shown in clearer detail than distant ones, this body of Christ appears to be rising from the sharply focused details of the lower body toward the less clearly focused surface of the torso and head, suggesting a movement from the space close to the viewer toward a more distant space.

The sculpture appears to be a metamorphosis of the body not only in space (close to far), but also in time (now to then): a visual metaphor for the change from the death of the body in the present to the life of the spirit in the eternal. A Resurrection.

This is a complex piece, a composite of themes of the Deposition, Lamentation, Pietà and Entombment gestures quoted and transformed into something new. It was too enigmatic, idiosyncratic, and personal to become a template for future artists to follow. Because it was left unfinished at the time of his death, this great work by Michelangelo was almost forgotten for centuries.

But what if its contradictions, its fragmentation, and conflicting styles and finish were the essence of the work? What if the meaning of the work was not completion but the process of transformation? A transformation not in the literal sense, but a more essential and imaginative or spiritual metamorphosis, an exceptional old man’s power to shape stone into a form of complex ideas and emotions.

THE HINGE

A hinge is a turning point, a pivot for opening and closing a door, a door between one space and another – in the case of the Rondanini Pietà, between one mode of thinking and another. Michelangelo closes the classical vocabulary of his whole career and opens the possibility for a new visual language in the quest to understand the human condition.

His last sculpture embodies not just conflict, which he had developed in a great number of figures both in sculpture and painting, but something more abstract – irresolution, the visual realization of “not knowing”. While Christian faith calls for trust in dogma and the rejection of doubt, this work is the manifestation of quest, of search, of uncertainty.

This is a work in a new, modern spirit. Not Christian certainty and doctrine or classical Platonic rationality and measured coherence, but inconsistency, fragmentation, the transitional and conditional perception of meanings within any proposition. Not knowing.

What is life? What is death? Fighting against the limited time and strength left to him, the aged Michelangelo struggled physically and mentally to convey this insight of complexity and indeterminacy using his preferred medium – the obdurate material of stone.

This is part of the testament of the Rondanini Pietà, at least as far as I have been able to reflect on it. Barely commented on at Michelangelo’s death, it has been preserved long enough to emerge as one of the most significant artworks we have from his or any other hand.

There were no immediate heirs to this radical work by Michelangelo. Not in the following periods of Italian art, in the Mannerist or Baroque or Rococo periods, which, while pushing the naturalistic underpinnings of the Renaissance with elaborated figurative depiction and vivid details, did not break with naturalism. The heirs I think of were artists who tried to take figurative art beyond illustration to some intangible and concealed levels of meaning, which in the modern period came to be called expressionism.

One post-Renaissance painter that comes to mind is El Greco, an artist concerned with the spiritual meaning of life who contrived idiosyncratic figures to depict mysteries, the strange.

The true heirs of the Rondanini Pietà came much later, in the modern era. I think of how these painters depicted the human image: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Soutine, Kokochka, Chagall, Klee, Matisse in some works, Francis Bacon, and of course Picasso. Especially Picasso. And in sculpture: some works by Rodin, like his Balzac, Giacometti, Henry Moore, and again Picasso. Especially Picasso.