CLOCK 1980

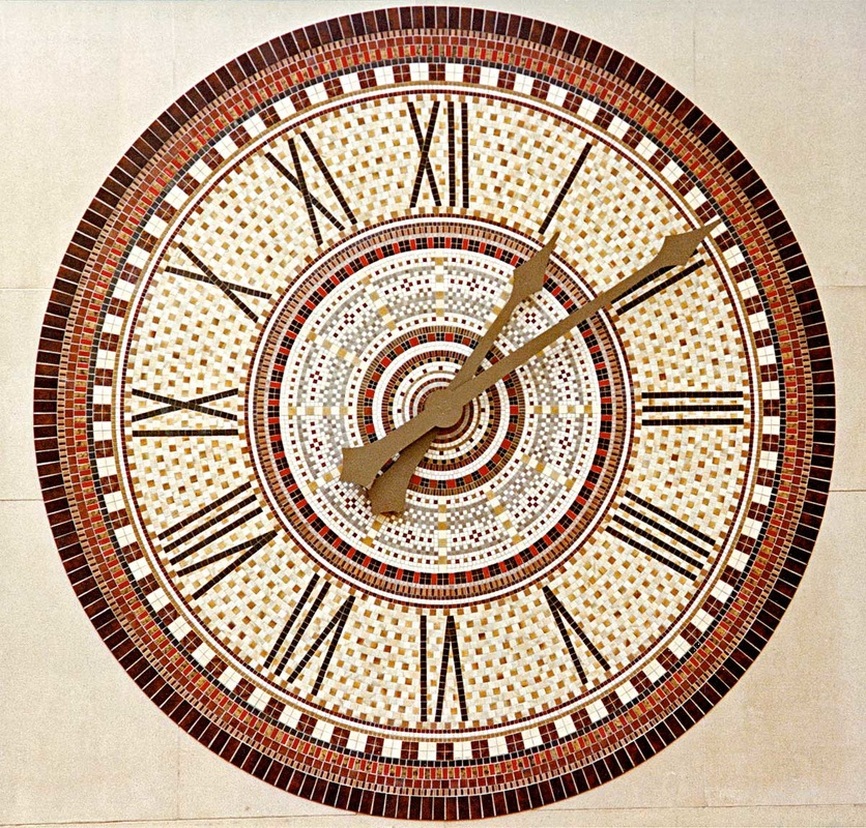

Clock 24 ft. diameter, 452 sq.ft., c.13,900 tiles (various sizes, 1"X1” to 4"x8")

One Market Plaza, San Francisco, CA

One Market Plaza, San Francisco, CA

BACKGROUND

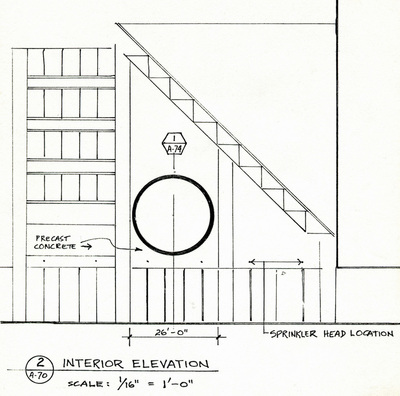

The Van Doren Gallery in San Francisco was retained by One Market Plaza to select artworks for the various public spaces in the building complex. They presented several proposals for artwork to be placed on the large triangular concrete wall on the southwest corner of the Galleria, adjacent to the Market Street Lobby, but for two years all had been rejected. In 1978, when I contacted the Van Doren Gallery, I was asked to consider designing an artwork for that space.

My first impression upon seeing the Galleria was that it would be difficult to design a piece to fit into such a large triangular space. The wall started at about 16 feet above ground level, and was so high that no one walking by would have occasion to look at whatever was to be put up there.

I watched the lunch hour rush in the building, and saw no one look up. As I was standing across from the wall, considering ideas for a design, someone asked me for the time, and I had my design idea. I went looking for a clock in all of the public lobbies, on the walls of the many businesses fronting on the Galleria, in the restaurant opposite the wall I had to deal with, and found none. A large, attractive mosaic-faced clock seemed the perfect solution for enhancing that blank wall.

The clients wanted a non-figurative design, and the clock would be that. Being functional, the clock would give people a reason to look up at it. Its circle would be the perfect form for the triangular wall space. It would also relate to the many circular elements in the Galleria: the restaurant across from the wall had a large circular fountain; the tiles on the vast floor were in concentric circles centered on the fountain, and even the small trees were planted in circular grill-topped spaces. And outside the building, on the other side of the Embarcadero, was the tower of the Ferry Building with its large clocks plainly visible above the freeway.

DESIGN

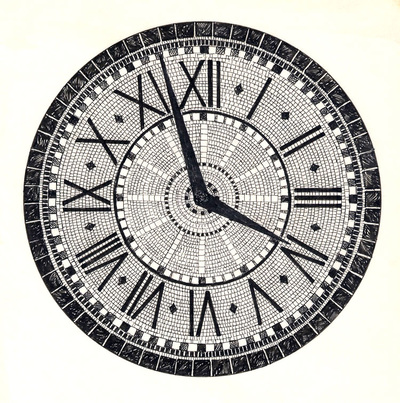

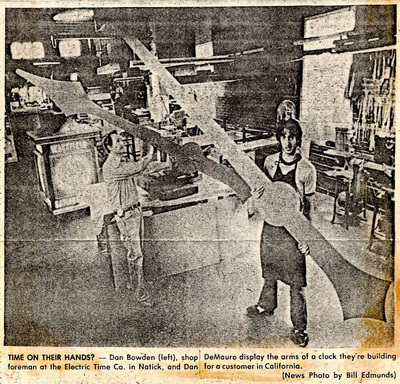

I submitted my proposal for a ceramic tile mosaic faced clock, with drawings of the general design. The clock face was to be 24' in diameter, to fit within the pattern of the pre-cast concrete joint lines of the wall. I also found a clock-maker who assured me that he could get the clockworks and hands to fit my design. The idea was accepted, and I had to submit a model in color. I made a 12'-long section, showing one number from the center of the clock to the outer edge, using the actual tiles I would use in the finished clock. All my tile choices were made at this stage, the colors, sizes and patterns, and when the clients accepted this, in December 1978, I thought that I was home free. I was wrong.

The Van Doren Gallery in San Francisco was retained by One Market Plaza to select artworks for the various public spaces in the building complex. They presented several proposals for artwork to be placed on the large triangular concrete wall on the southwest corner of the Galleria, adjacent to the Market Street Lobby, but for two years all had been rejected. In 1978, when I contacted the Van Doren Gallery, I was asked to consider designing an artwork for that space.

My first impression upon seeing the Galleria was that it would be difficult to design a piece to fit into such a large triangular space. The wall started at about 16 feet above ground level, and was so high that no one walking by would have occasion to look at whatever was to be put up there.

I watched the lunch hour rush in the building, and saw no one look up. As I was standing across from the wall, considering ideas for a design, someone asked me for the time, and I had my design idea. I went looking for a clock in all of the public lobbies, on the walls of the many businesses fronting on the Galleria, in the restaurant opposite the wall I had to deal with, and found none. A large, attractive mosaic-faced clock seemed the perfect solution for enhancing that blank wall.

The clients wanted a non-figurative design, and the clock would be that. Being functional, the clock would give people a reason to look up at it. Its circle would be the perfect form for the triangular wall space. It would also relate to the many circular elements in the Galleria: the restaurant across from the wall had a large circular fountain; the tiles on the vast floor were in concentric circles centered on the fountain, and even the small trees were planted in circular grill-topped spaces. And outside the building, on the other side of the Embarcadero, was the tower of the Ferry Building with its large clocks plainly visible above the freeway.

DESIGN

I submitted my proposal for a ceramic tile mosaic faced clock, with drawings of the general design. The clock face was to be 24' in diameter, to fit within the pattern of the pre-cast concrete joint lines of the wall. I also found a clock-maker who assured me that he could get the clockworks and hands to fit my design. The idea was accepted, and I had to submit a model in color. I made a 12'-long section, showing one number from the center of the clock to the outer edge, using the actual tiles I would use in the finished clock. All my tile choices were made at this stage, the colors, sizes and patterns, and when the clients accepted this, in December 1978, I thought that I was home free. I was wrong.

FABRICATION

My original proposal called for mounting the tiles on plywood sections. The panels would then have been bolted to the wall, the bolts covered with tiles, and the joints grouted. Though initially accepted as proposed, this method was subsequently refused because of fire regulations. The City called for flame- and smoke-retardant plywood. Then I was advised that I should not bond the tiles to such treated wood because the mastic manufacturers had no tests for such use. This strict code consideration was the major, though not the only, factor in delaying the project for many months. Finally I was left with the alternative of setting the tiles directly onto the wall.

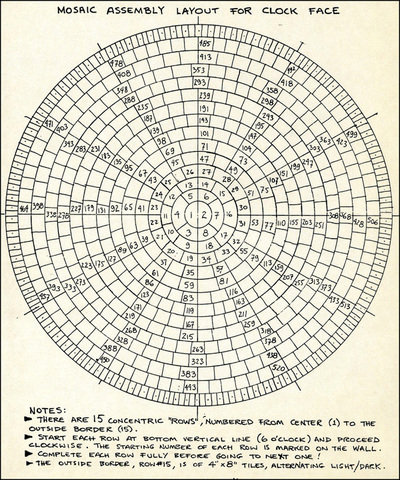

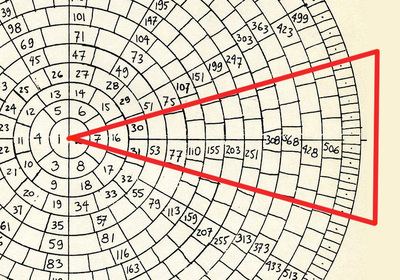

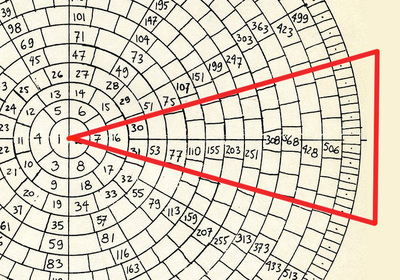

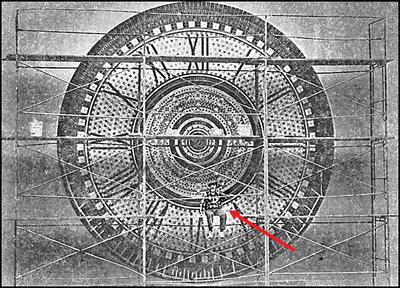

I made the entire mosaic in 12 sections of 30-degree wedge shapes, each wedge representing one number of the clock. I drew exact patterns on heavy kraft paper, marking the rows of tiles in concentric arcs, each arc drawn to the size of the tiles in that row.

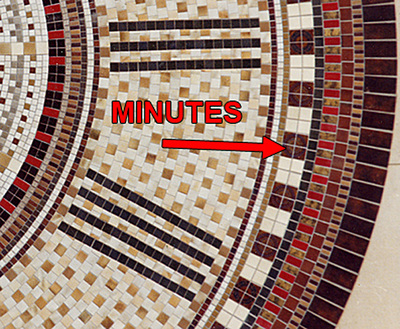

I then laid out the tiles on the paper pattern, staggering the edges of the sections to mesh with adjacent sections without showing seams. The tiles were then covered with clear Contact paper to hold them in place. Clear Contact paper (I later used clear packing tape) goes on dry and clean, and any dislocation of the tiles can be seen and readily adjusted.

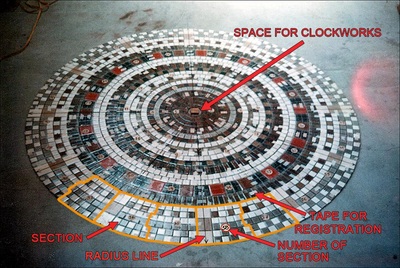

On each wedge section I marked a radius line from the apex to the outside arc, centered on each number. These lines would register with the 12 radiating lines I drew on the wall at the time of installation, and they proved very useful in maintaining accuracy.

I then marked off the concentric arcs of each tiled wedge into smaller sections, numbered each section according to the drawn plan, and taped small tabs of masking tape across all the lines to be cut. These tabs were cut through as the sections were cut, and served as registration marks when the sections were re-assembled on the wall. Their perfect alignment at installation guaranteed the success of the project.

Even small errors in alignment would end up in gaps when the ends of the circling rows met their beginnings, and there would be no way to correct the problem. As it turned out, the very skeptical professional tile setters finished their work two days ahead of schedule, amazed at the precision I had built into the process.

My original proposal called for mounting the tiles on plywood sections. The panels would then have been bolted to the wall, the bolts covered with tiles, and the joints grouted. Though initially accepted as proposed, this method was subsequently refused because of fire regulations. The City called for flame- and smoke-retardant plywood. Then I was advised that I should not bond the tiles to such treated wood because the mastic manufacturers had no tests for such use. This strict code consideration was the major, though not the only, factor in delaying the project for many months. Finally I was left with the alternative of setting the tiles directly onto the wall.

I made the entire mosaic in 12 sections of 30-degree wedge shapes, each wedge representing one number of the clock. I drew exact patterns on heavy kraft paper, marking the rows of tiles in concentric arcs, each arc drawn to the size of the tiles in that row.

I then laid out the tiles on the paper pattern, staggering the edges of the sections to mesh with adjacent sections without showing seams. The tiles were then covered with clear Contact paper to hold them in place. Clear Contact paper (I later used clear packing tape) goes on dry and clean, and any dislocation of the tiles can be seen and readily adjusted.

On each wedge section I marked a radius line from the apex to the outside arc, centered on each number. These lines would register with the 12 radiating lines I drew on the wall at the time of installation, and they proved very useful in maintaining accuracy.

I then marked off the concentric arcs of each tiled wedge into smaller sections, numbered each section according to the drawn plan, and taped small tabs of masking tape across all the lines to be cut. These tabs were cut through as the sections were cut, and served as registration marks when the sections were re-assembled on the wall. Their perfect alignment at installation guaranteed the success of the project.

Even small errors in alignment would end up in gaps when the ends of the circling rows met their beginnings, and there would be no way to correct the problem. As it turned out, the very skeptical professional tile setters finished their work two days ahead of schedule, amazed at the precision I had built into the process.

INSTALLATION

When the mosaic was completed, all of the 526 numbered tile sections plus the 204 large outside edge tiles were packed into 30 boxes, and we drove them to One Market Plaza.

The clock was installed in August of 1979. First a 3" hole was drilled in the wall at the center of the clock, through which the shaft of the clockworks would go from the mechanism mounted behind the wall to the hands in front of the tiles. Using this hole as center, we scribed the 15 concentric circles of the tile section rows on the wall, using a pre-measured paper drywall tape and a pencil. Then we snapped the 12 radii in chalk, at exactly 30 degrees, centered on the numbers' placement. The number of the first tile section to be set in each row was written on the wall, at the 6 o'clock position, where each row was to begin. Once this grid was drawn, the professional tile-setters we had hired (I did not have the required license and insurance to set the tiles myself) simply set the tile sections in sequence, row by row, from the inside out, in a latex mastic. The radii on the wall lined up with those on the tile sections, the masking tape registration marks aligning each section with the adjacent sections. Each row worked perfectly, and the entire tile face was set in less than three days. Two short days for removing the Contact paper, grouting, and cleaning, and the tile work was done.

When the mosaic was completed, all of the 526 numbered tile sections plus the 204 large outside edge tiles were packed into 30 boxes, and we drove them to One Market Plaza.

The clock was installed in August of 1979. First a 3" hole was drilled in the wall at the center of the clock, through which the shaft of the clockworks would go from the mechanism mounted behind the wall to the hands in front of the tiles. Using this hole as center, we scribed the 15 concentric circles of the tile section rows on the wall, using a pre-measured paper drywall tape and a pencil. Then we snapped the 12 radii in chalk, at exactly 30 degrees, centered on the numbers' placement. The number of the first tile section to be set in each row was written on the wall, at the 6 o'clock position, where each row was to begin. Once this grid was drawn, the professional tile-setters we had hired (I did not have the required license and insurance to set the tiles myself) simply set the tile sections in sequence, row by row, from the inside out, in a latex mastic. The radii on the wall lined up with those on the tile sections, the masking tape registration marks aligning each section with the adjacent sections. Each row worked perfectly, and the entire tile face was set in less than three days. Two short days for removing the Contact paper, grouting, and cleaning, and the tile work was done.

The clockworks were a separate problem and proved to be more troublesome to install than the tiles. The space behind the clock's center, where the mechanism was to be mounted, was in the vast computer center of the Southern Pacific Railroad, the heart of its system for 12 western states, a highly sensitive area open only to authorized persons. The clockworks were to be mounted on the wall between the actual ceiling and the tiles of the dropped acoustic ceiling over one of the many huge computers. Everyone was very nervous about this.

Then the motor mounting had to be modified because structural beams holding the wall panels blocked its space. Then the shaft had to be shortened, and the hands, when finally mounted, were out of alignment by 15 minutes, and had to be re-mounted. But finally all components were installed and working, including a remote reset control, which could reset the time on the clock in case of power failure or change from standard to daylight savings, without someone having to climb up the face of the wall to do it.

EARTHQUAKE

On October 17, 1989, a 6.9 earthquake hit Northern California causing damage throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. Some time later I was notified that the clock had sustained some minor damage, and tiles that were set along one of the seams in the wall had broken loose. Fortunately the rest of the tiles and the clockworks and hands were intact. I collected and sent a parcel of replacement tiles with which the mosaic was repaired.

Then the motor mounting had to be modified because structural beams holding the wall panels blocked its space. Then the shaft had to be shortened, and the hands, when finally mounted, were out of alignment by 15 minutes, and had to be re-mounted. But finally all components were installed and working, including a remote reset control, which could reset the time on the clock in case of power failure or change from standard to daylight savings, without someone having to climb up the face of the wall to do it.

EARTHQUAKE

On October 17, 1989, a 6.9 earthquake hit Northern California causing damage throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. Some time later I was notified that the clock had sustained some minor damage, and tiles that were set along one of the seams in the wall had broken loose. Fortunately the rest of the tiles and the clockworks and hands were intact. I collected and sent a parcel of replacement tiles with which the mosaic was repaired.

REMOVAL

I was pleased that the clock kept ticking and assumed it was set for a long and well-maintained life. Wrong again. In 1994 I was in the process of installing another project when I got a call to inform me that One Market Plaza was slated for a major renovation and that the clock would be removed from the wall. In accordance with California law, an artist had to be notified if his public work was to be moved from its original site, and this was my notice. Would I want my artwork back? Of course this was absurd since removing the tiles from the wall in effect destroyed the mosaic, so I said no thanks.

I did contact the architect in charge of the renovation to propose an alternative piece for the wall, but after their initial interest in my drawings and models, my proposal was rejected. In the new design, the wall was left blank.

I was pleased that the clock kept ticking and assumed it was set for a long and well-maintained life. Wrong again. In 1994 I was in the process of installing another project when I got a call to inform me that One Market Plaza was slated for a major renovation and that the clock would be removed from the wall. In accordance with California law, an artist had to be notified if his public work was to be moved from its original site, and this was my notice. Would I want my artwork back? Of course this was absurd since removing the tiles from the wall in effect destroyed the mosaic, so I said no thanks.

I did contact the architect in charge of the renovation to propose an alternative piece for the wall, but after their initial interest in my drawings and models, my proposal was rejected. In the new design, the wall was left blank.